[Historical Culinary Reconstruction- To make two beverages for invalids]

Table of Contents

Date and Time:

2017.January.24, 7:00 pm- 8:00 pm

Location:Butler Library, Coffee placeSubject: Discussion on the manuscript and things need to purchase

The recipes we chose was making beverages for invalids. The recipes read:

1. Sweet Tisane: Take water and boil it, then add for each sixth of a gallon of water one good bowl of barley, and it does not (or it does matter?-Trans.) if it still has its hulls, and get two parisis' worth of licorice, item, or figs, and boil it all until the barley bubbles; then let it be strained in two or three cloths, and put in each goblet a large amount of rock-sugar. This barley is good to feed to poultry to fatten them.

Note that good licorice is the youngest, and when cut is a lively greenish colour, and if it is old it is more insipid and dead, and dry.

2. Bouillon: To make four sixths of bouillon, you need half a brown loaf of bread costing one denier, yeast bread, raised three days, item, bran, a good quarter of a bushel, and put five sixths of water in a pan, and when it boils, put the bran in the water and boil until it all reduces by a fifth or more; then take it off the fire and let it cool until it is just warm, then strain through a sieve or cloth, then soak the leavened bread in water and put it in a cask, and leave it for two or three days to work; put in the cellar and leave to clarify, and then drink.

Item, if you want to make it better, you should add a pint of honey, well boiled and well skimmed.

Original French text here:

Christopher and I decided to work together as we both live near the campus. We got the assignment at the Jan. 23 class, and plan to meet at Jan. 24 to go shopping for the materials needed. We both undertook preliminary research on the recipes at home. I found some sentences, materials and measurements are quite confusing.

First, I know the licorice quite well as it is a common herb used in Chinese medicine, known as as sweet grass (甘草) that can be used in a prescription for mediating and facilitating the property and efficacy of all the other ingredients, and, has curative effects for cough, ulcer, inflammation, digestive problems and constipation when applied in its own right. However, the medicinal part of the licorice is the root, and root is brown or reddish brown on the surface and light brown (the color of wood) in the core. Whether fresh or dried, the root is not green.

At first, I thought the licorice could possible referred to the licorice seeds, which could be a match to the barley (also seeds). After I went back home, I asked my flatmates, an American couple in their fifties, if they knew about licorice. They told me the first thing came into their mind is a kind of candy. When I said it should be a kind of herb, the lady showed me one bottle from her collection of spices, labeled "Star Anise, come from China, with a flavor of licorice". Star Anise is one of the basic spices in Chinese cuisine, and also a herbal medicine. Whereas the label shows the flavor of licorice is more familiar to Americans than that of the anise. When I search the relationship between licorice and anise, I came across the item on "comfit" in wikipedia which links to a reference to an early modern British recipe manuscript (in Old English? not sure), "BL MS Harley. 2378" preserved at British Library, Harleian collection.

Original manuscript here

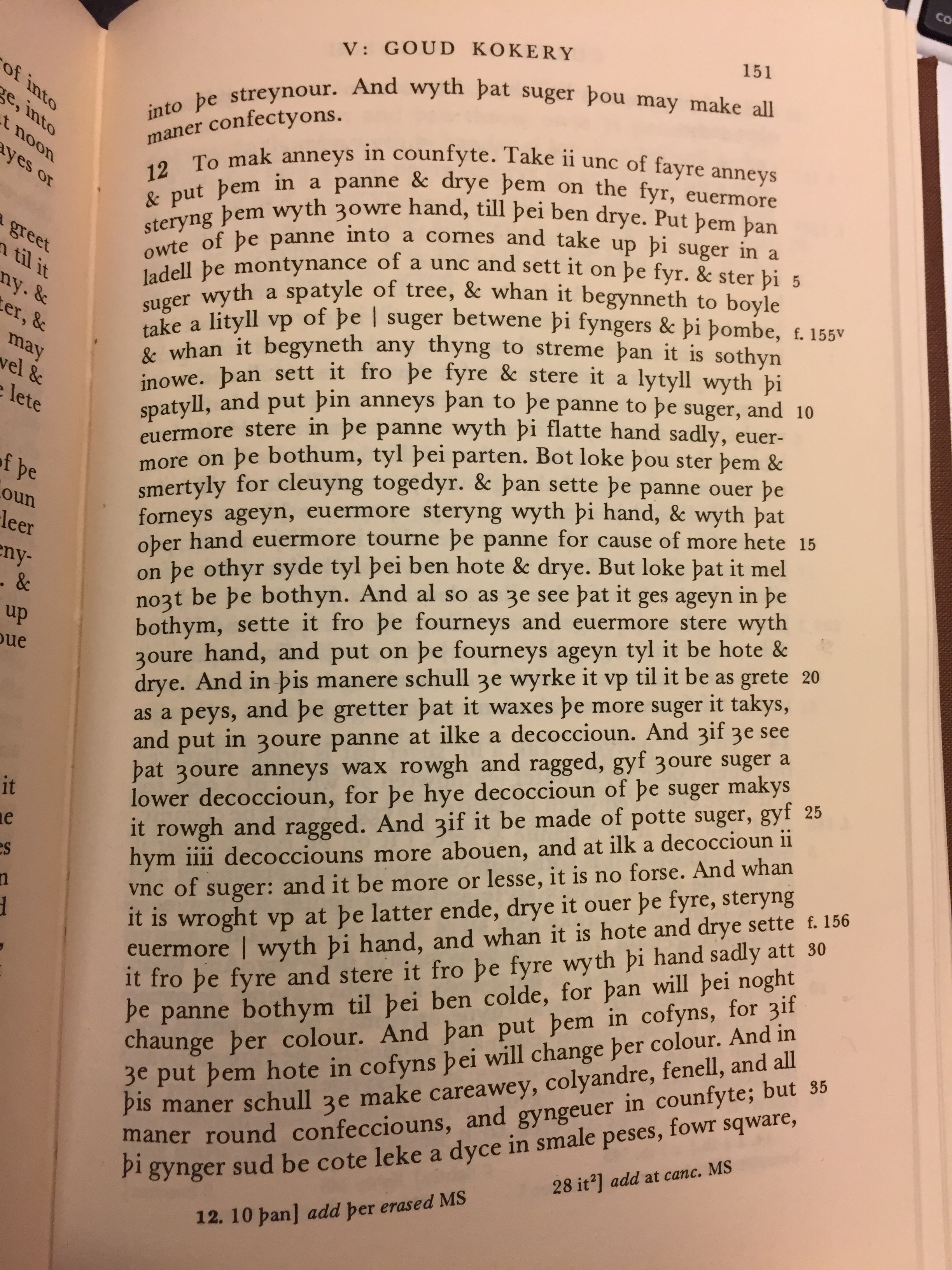

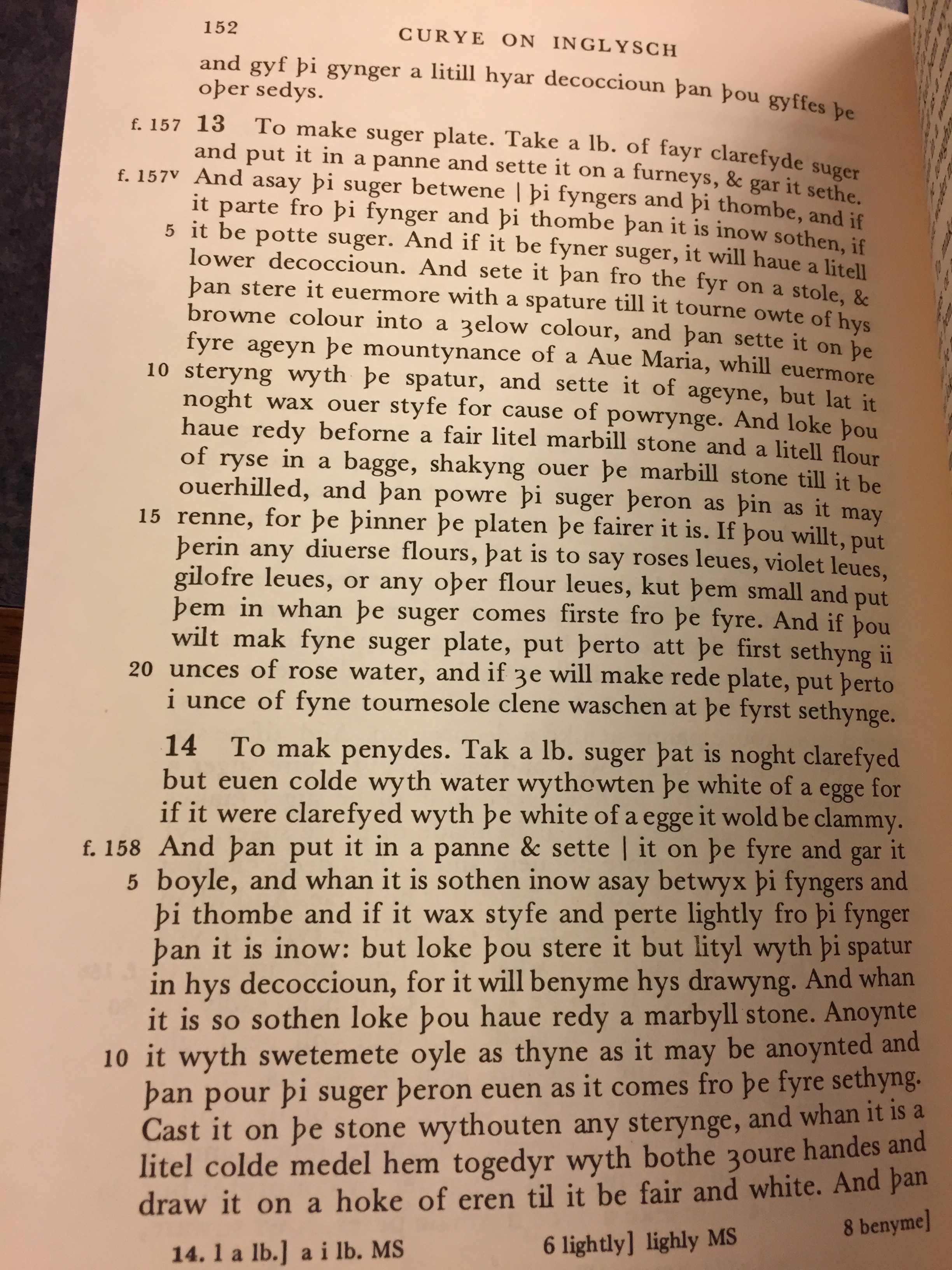

Harley MS 2378-f.155r

Harley MS 2378-f.155v

Harley MS 2378-f.156r

There's also a transcription available at Constance B. Hieatt and Sharon Butler eds., Curye on Inglysch: English Culinary Manuscripts of the Fourteenth Century (Including the Forme of Cury), London: Oxford University Press, 1985, pp. 151-152.

(I didn't look into the original manuscript at the initial stage, while continued the work when I edited the lab notes on Feb. 6, 2017)

The recipe shows how to make comfit with anise, but also mentions other ingredients like fennel, caraway, coriander, and diced ginger could also be used to make comfits, which suggests what called licorice comfit is not necessarily made from licorice, but other spices with a licorice flavor.

It's a bit far away from the point. Then I continued to look more into the use of licorice in medieval and early modern Europe. I found a brief history of licorice written by Mishelle Knuteson, which is a synthesis of relevant information from several works on natural healing and herbal medicine rather than an original research, showing the wide use of licorice "root" in the different ancient civilizations around the globe. (link here history of licorice)

The book The Cultural History of Plants also has an item on licorice with a brief description of the use of licorice "root" in medieval Europe. (Sir Gillian Prance and Mark Nesbitt eds., The Cultural History of Plants, New York: Rutledge, 2005, p.220) It's clear that when the medicinal use of licorice was referred, the part for usage would always be the root. Then I figured the "greenish" in the note of the original recipe could be interpreted as slightly green which could be possible when the root is young and fresh. But what I can get from the herbal shop is the dried roots. I also notice that the Latin name for the licorice used in Europe is Glycyrrhiza glabra, while the Chinese one is Glycyrrhiza uralensis. They are different species from the same family. In order to reconstruct the recipe as original as possible, I cannot buy the licorice root from a Chinese herbal shop.

A scientific report from European Medicines Agency provides detailed information about the historical data and clinical use of different kind of licorice. See here: Assessment report on Glycyrrhiza glabra L. and/or Glycyrrhiza inflata Bat. and/or Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch., radix

I checked the sourcing information on the class wiki and found the herbal shop "Flower and Power"(the inventory of their bulk herbs here: Flower and Power). I browsed their inventory on the website and found they have the Glycyrrhiza glabra. Then I called and asked the price. It's $4.25 per ounce.

Second, I find the word "parisis" confusing as it seems like a ancient French currency which I can not find much information about. The English translator did not provide any further information about it either, while he did give suggestions for the conversion of measurements in the second recipe. I tried to identify the original text in the French imprints, and found a footnote stating the parisis was a small silver coin worth a quarter of one denier. (p.238) However, this does not make things clear.

Third, the bread mentioned in the second recipe is unclear. What is a brown bread? Here is good webpage about all kinds of bread in history and their references(link here: Food Timeline: Bread) From this page, brown bread refers to the kind of bread made from whole wheat floor, or rye floor, or a mixture of both, which, though considered health food at present, was the food for common and poor people. There's a quote from The Story of Bread described the consume of different kinds of bread in different social groups in European history, "There has always been a certain snobbery about the colour of bread. For centuries the eating of white bread was considered a mark of social position...The Romans were probably responsible for this. The senators, the senior officers of the army and others took pride in providing their guests with white bread made from wheaten flour. Dark bread made from millet, barley, and other coarse grains was generally regarded as the food of the working class...During the fourteenth century, even the peasant classes began to develop a taste for wheaten flour and there was a growing demand for better, which meant whiter, bread...But this demand was not to be met fully for a long time to come; in the main the poorer people had to be content with rye bread or maslin, made from a mixture of rye and wheat flours." (Ronald Sheppard and Edward Newton, The Story of Bread, London: Routledge& Kegan Paul, 1957, pp.69-75.) At the beginning, I misunderstood the part "yeast bread, raised three days" as a further processing of the bread, which had been corrected by Christopher during our discussion.

It seems the two recipes were typically made for “poor” invalids. They just require very simple and cheap food, then boil and strain the juice, possibly in order to make the beverage as nutritious and digestible as possible from the common ingredients. The rock-sugar and honey were used to make them more enjoyable when drink, and sweet could be a good thing to provide energy for the invalid in the time when the food is insufficient.

As both of us found the texts confusing, we decided to meet and discuss first before buying the ingredients. We then changed our plan an meet at Butler Library instead.

Christopher told me the original text are written in very archaic French that he can not fully understand. We went through the whole English text and identified all the things we need to buy, including: barley, licorice, figs, cloth for straining, rock-sugar, whole wheat bread, bran, honey. We split up the work. I'm going downtown to get the licorice, and Christopher will buy all the other things which could be get easily around the neighborhood. As I can only have the time to buy the licorice at Thursday, and I'm going to Boston to attend the NEAAS conference, and Christopher also had a very buy week. We decided to make the second recipe first at Wednesday night, and make the first one at Saturday night after I'm back from Boston. Christopher has a kitchen in his apartment, we decide to do the work there as I need to get the permission from my flatmates before having friends over.

I went to Westside market at the conner of Broadway and W 110 St. on my way back home, and got the bran and figs. And Christopher got everything else except the cloth. Even if I have a sieve, I thought it would be better if we get the cloth and made a comparison between the two instruments for straining. I figured the type of cloth we need is called cheese cloth, and decided to find it around neighborhood the next day. (Target has it, but the store is to far away)

Note: A further reading at Feb. 9, more than two weeks after this was done, facilitated me to reconsider the type of cloth and the difference between cloth and sieve. The paragraph reads: "The 'green ointment for sores or salve' in the Okeover volume requires straining through a sieve: this line is annotated in the margin by another hand that directs it should be 'run...through a canvas strainer not wrung or squeeze at all' (Wellcome MS 3712, p.238). This observation is not only invaluable for what it says about practice-- specifying what the straining should comprise-- but for what it reveals about the material cultural technology of the kitchen. The annotator wanted to record the fact that straining through a metal sieve would not suffice: only careful running through a canvas bag (the forerunner of a modern jelly bag) would achieve the correct consistency for the salve." (Sara Pennell, "Perfecting Practice? Women, Manuscript Recipes and Knowledge in Early Modern England," ed. by Victoria E. Burke and Jonathan Gibson, Early Modern Women's Manuscript Writing: Selected Papers from the Trinity/Trent Colloquium, Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008, pp. 249-250)

Name: (Also the name of your working partner)

Date and Time:

2016.[Month].[Day], [hh]:[mm][am/pm]

Location:Subject:

Name: (Also the name of your working partner)

Date and Time:

2016.[Month].[Day], [hh]:[mm][am/pm]

Location:Subject:

ASPECTS TO KEEP IN MIND WHEN MAKING FIELD NOTES

- note time

- note (changing) conditions in the room

- note temperature of ingredients to be processed (e.g. cold from fridge, room temperature etc.)

- document materials, equipment, and processes in writing and with photographs

- notes on ingredients and equipment (where did you get them? issues of authenticity)

- note precisely the scales and temperatures you used (please indicate how you interpreted imprecise recipe instruction)

- see also our informal template for recipe reconstructions